Emotions in Childhood

EmoChi - Project

About

Humans are exceptionally social beings. Understanding others' emotions, as well as regulating one’s own emotions, are foundational skills that children acquire, and continuously build across development to successfully navigate the social world.

The goal of the EmoChi-project is to develop a knowledge-exchange hub to make research on emotional development accessible to children, parents, caretakers, and other stakeholders. We are looking to engage in a conversation around what we know about emotions in early childhood, and how we can use this knowledge to improve children's social competence. This website is designed to help parents learn more about emotions, encourage meaningful family conversations, and support children's emotional development.

The content of this website was created by the research team of the Social Foundations Lab at the University of Oxford.

The project was funded by Ferrero Int. from January 2024 to January 2026.

What is an emotion

Emotions play a key role in our everyday lives. They influence how we interact with other people and how we navigate our social environment. For example, fear might prompt us to avoid danger, while happiness can encourage social connection. However, despite their importance, emotions can be difficult to define. Most researchers agree that emotions are complex psychological and physiological reactions to internal events (thoughts, imaginations) and external events (situations and context).

Emotions can be characterised by:

-

Subjective experiences → The feelings we have when we experience an emotion.

-

Physiological responses → For example, sweating and changes in heartbeat or breathing, which can activate or deactivate the body depending on the situation.

-

Behavioural responses → This can include facial expressions and bodily movements

The development of emotions

Current research suggests that emotional understanding and perception develop significantly across childhood and into adulthood. Children tend to develop better emotion understanding skills in families that openly express emotions. Conversations about emotions and the child’s overall language development also enhance this understanding.1

As parents it is important to recognise that there are important differences between adults’ and children's recognition and understanding of emotions. Studies indicate that children, in their preschool years, begin with two broad emotion categories - 'feels good' and 'feels bad'. With development and experience, children gradually acquire more specific emotion categories, and their understanding becomes more adult-like.2

EMOTIVERSE PROJECT

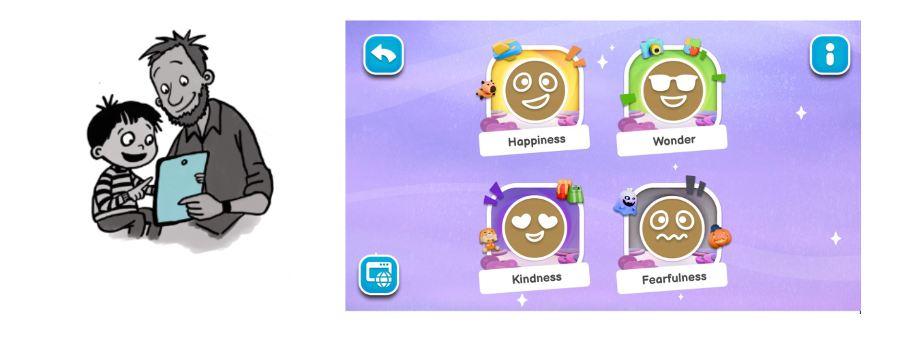

We have been working together with Gameloft and Ferrero Int. to integrate the content of this website within a game which introduces children to different emotions. The game follows an alien protagonist who wants to learn about human emotions.

The game is live on both the Google Play Store and the Apple App store. To explore the game, you can scan the QR code below! We have co-designed the game with our partners to feature educational elements to encourage conversations between children and their parents about feelings and emotions in everyday life.

Within the Applaydu world, we focus on 4 groups of emotions that have been particularly researched from a developmental perspective: happiness, kindness, fear, and wonder. Children get to choose an emotion to learn about through games with their alien friend, Quirk

Through the Winter months, there is also the option to learn about four additional emotions: awe, elevation, forgiveness and gratitude! In this edition of Emotiverse, children can make themed, digital cards for their loved ones. At the same time as encouraging them to think about the emotions and ways they can express them, children play games to help Quirk deliver a gift to a friend on his home planet.

There is also a pop-up button, in the bottom left corner, for both editions of the game to provide some bonus information about the emotion for each game for parents and children alike:

And if you would like to know more, you can find the full collection of fun facts and information for each emotion through the hyperlinks below!

Surprise (Wonder)

Research Team

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

Artwork

Illustrations provided by Allysa Adams

www.allysaadamsillustration.com

References

Development of emotions

- Ogren, Marissa, and Scott P. Johnson. "Factors facilitating early emotion understanding development: Contributions to individual differences." Human development 64, no. 3 (2021): 108-118.

- Widen, Sherri C. "Children’s interpretation of facial expressions: The long path from valence-based to specific discrete categories." Emotion Review 5, no. 1 (2013): 72-77.